Segment Anything Model (SAM)

The promptable foundation model revolutionizing zero-shot image segmentation through massive-scale training.

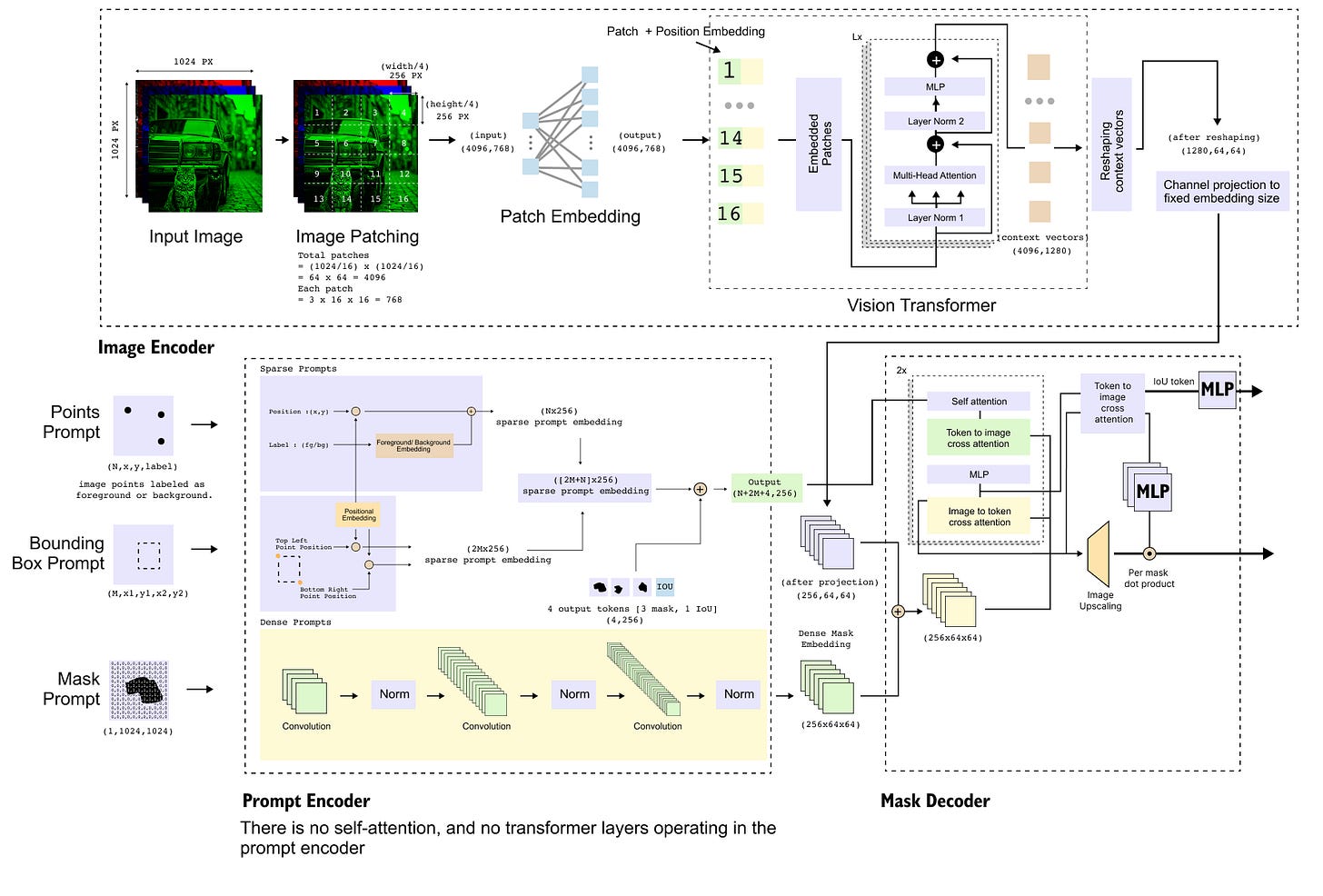

Figure 0: Detailed Architecture of the Segment Anything Model (SAM).

Table Of Content

Introduction to the Segment Anything Model (SAM)

High-Level Architecture of the Segment Anything Model

Prompting Mechanisms in the Segment Anything Model

How the Dataset for SAM Was Created (Segment Anything 1B)

Image Encoder in the Segment Anything Model

Masked Autoencoder Pretraining for the SAM Image Encoder

Prompt Encoder in the Segment Anything Model

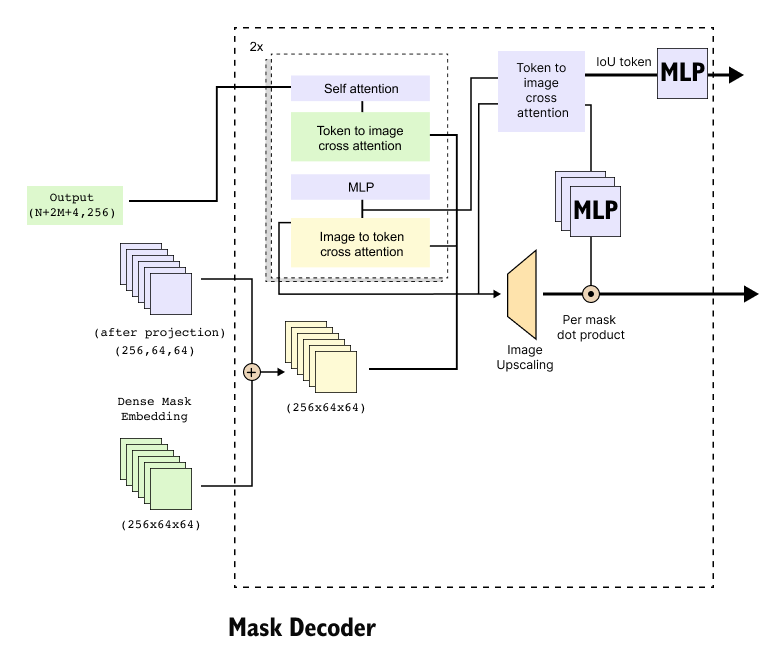

Mask Decoder

Conclusion Perspective on SAM

1.1 Introduction to the Segment Anything Model (SAM)

Figure 1.1: High-level overview of the Segment Anything Model (SAM), illustrating how an input image is processed along with user prompts to generate one or more segmentation masks.

Image segmentation has long been considered one of the most challenging problems in computer vision. Unlike image classification, which assigns a single label to an entire image, or object detection, which localizes objects using bounding boxes, segmentation requires pixel-level understanding—every pixel in the image must be assigned to a meaningful region or object. This level of precision is essential in applications such as medical imaging, autonomous driving, robotics, image editing, and scientific analysis.

Traditional segmentation models are typically task-specific and class-specific. For example, a model trained to segment cats and dogs cannot directly generalize to segment trees, vehicles, or furniture without retraining on new annotated data. Moreover, collecting high-quality segmentation masks is expensive and time-consuming, making large-scale generalization difficult. These limitations motivated the need for a general-purpose, reusable, and flexible segmentation model.

This is precisely the gap addressed by the Segment Anything Model (SAM).

The Meta AI Research team introduced the Segment Anything Model in 2023 as a foundational vision model for segmentation. Much like how large language models serve as general-purpose foundations for text, SAM is designed to serve as a universal segmentation backbone that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal or no retraining. The paper rapidly gained attention within the research community, accumulating thousands of citations in a short span of time, and has since influenced many follow-up works in vision and multimodal learning.

At a high level, SAM reframes segmentation as a promptable task rather than a fixed prediction problem. Instead of asking the model to segment only predefined object categories, SAM allows users to guide the segmentation process through prompts.

These prompts can take several forms. A user may provide a point click on an object of interest, indicating a specific spatial location that the model should focus on. Alternatively, the prompt can be a rough bounding box drawn around a region, conveying a vague but useful prior about where the target object lies within the image. In more complex scenarios, the user may supply a coarse or approximate mask, roughly shading the area of interest and asking the model to refine it into an accurate, pixel-level segmentation. Additionally, although the Segment Anything Model does not natively accept text as input, textual descriptions can be incorporated indirectly by coupling SAM with external vision–language models, enabling segmentation based on semantic instructions expressed in natural language.

Given an input image and a prompt, SAM predicts one or more segmentation masks that best correspond to the user’s intent. This interaction paradigm makes the model highly flexible and suitable for both automated pipelines and human-in-the-loop systems.

Another defining characteristic of SAM is its ability to handle ambiguity in user intent. A single click on an image can be interpreted in multiple valid ways—for instance, selecting an entire object, a part of an object, or a smaller sub-region. To address this, SAM produces multiple candidate masks in a single forward pass, allowing the user or downstream system to choose the most appropriate one. This design choice reflects a practical understanding of how segmentation is used in real-world scenarios.

Behind this capability lies an unprecedented training effort. SAM was trained on a massive dataset containing millions of images and over a billion segmentation masks, covering a diverse range of objects, scenes, and visual concepts. Crucially, the model is class-agnostic, t does not rely on fixed semantic labels during inference. Instead, it learns a rich notion of “objectness” and spatial coherence, enabling it to segment previously unseen categories.

In the next section, we will move beyond this conceptual overview and introduce the architecture of SAM, examining how its image encoder, prompt encoder, and mask decoder work together to enable promptable, high-quality segmentation at scale.

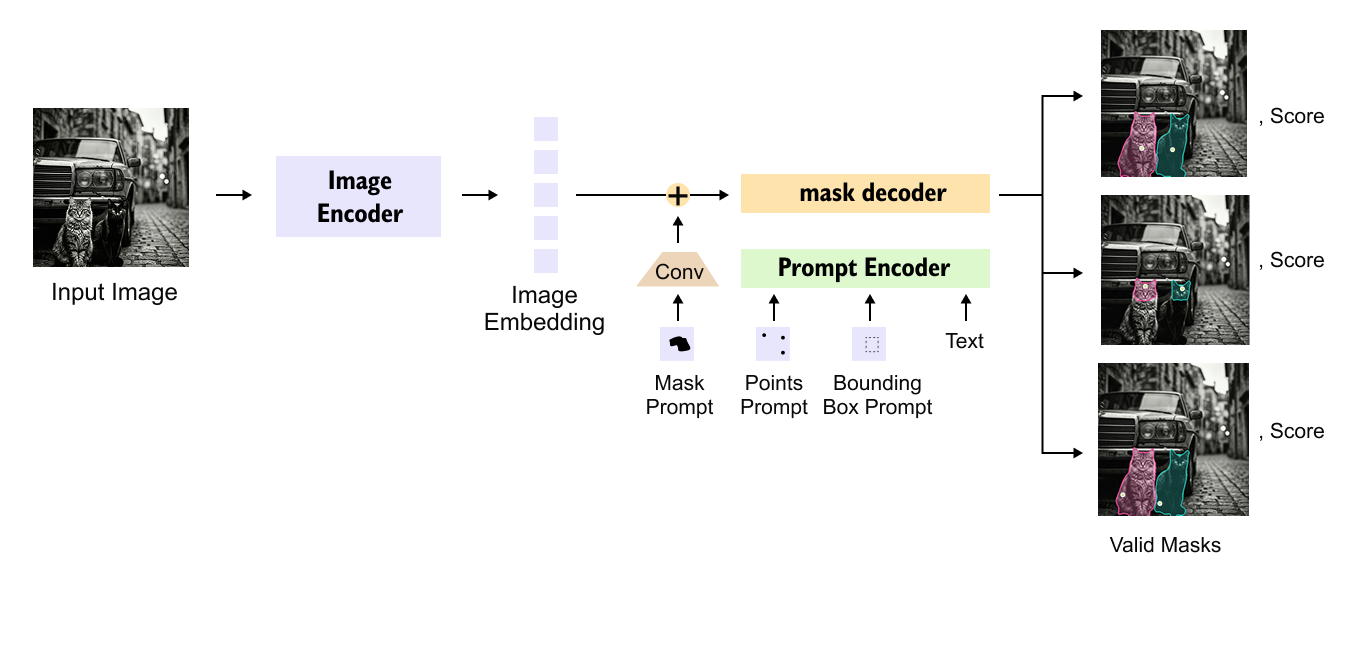

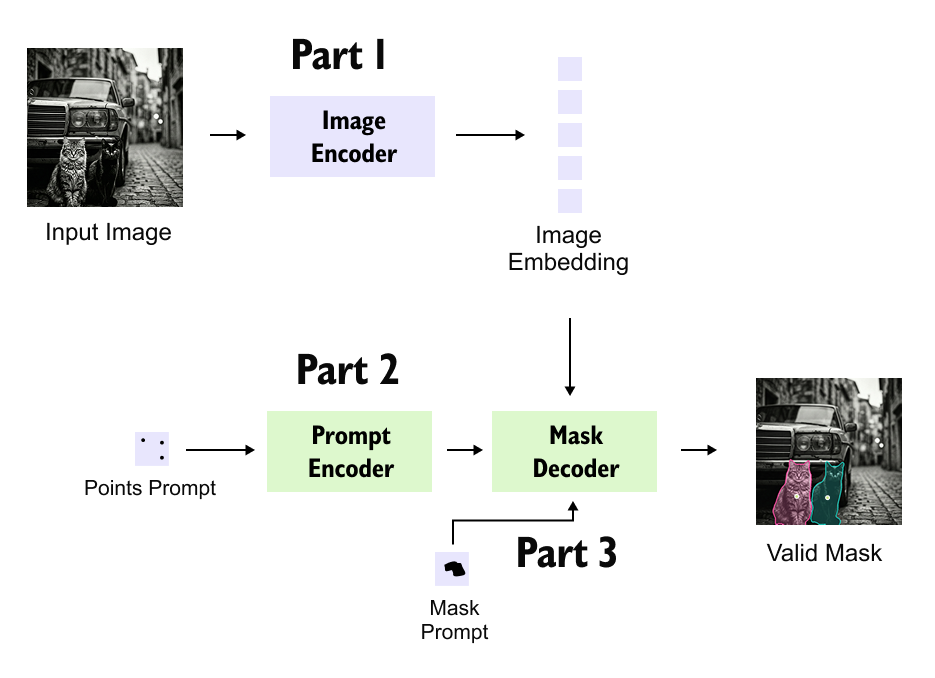

1.2 High-Level Architecture of the Segment Anything Model

Figure 1.2: High-level architecture of the Segment Anything Model (SAM), showing the image encoder, prompt encoder, and mask decoder. The mask decoder integrates image embeddings, prompt embeddings, and initialized mask tokens to produce multiple valid segmentation masks with associated confidence scores.

At first glance, the architecture of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) appears deceptively simple. However, this simplicity is the result of a carefully designed abstraction that unifies multiple input modalities, images and prompts,into a single, coherent segmentation pipeline. At a high level, SAM is structured around three core components: an image encoder, a prompt encoder, and a mask decoder. Together, these components enable promptable, class-agnostic, and flexible segmentation.

The starting point of the pipeline is the input image. Since SAM is designed as a foundation model, the image is first transformed into a rich, high-dimensional representation that captures global context as well as fine-grained spatial details. This transformation is performed by the image encoder, which converts the raw image into a dense image embedding. Conceptually, this embedding can be viewed as a structured feature map that encodes “what is present” and “where it is present” in the image. Importantly, this step is independent of any specific segmentation task or object category.

In parallel, SAM processes the user-provided prompt through a dedicated prompt encoder. Prompts can take different forms, such as points, bounding boxes, or coarse masks, but regardless of their modality, they must be mapped into a common embedding space. The role of the prompt encoder is precisely this: to transform heterogeneous prompt signals into prompt embeddings that are compatible with the image embedding. These embeddings do not directly encode semantic class labels; instead, they encode intent, that is, what region or object the user is interested in segmenting.

The most critical component of SAM is the mask decoder, which is responsible for integrating multiple streams of information and transforming them into precise segmentation outputs. Specifically, the mask decoder jointly operates on three distinct inputs. First, it receives the image embedding generated by the image encoder, which encodes rich visual and spatial information about the entire image. Second, it takes as input the prompt embedding produced by the prompt encoder, which represents the user’s intent in a form that is compatible with the visual features. Finally, the decoder is initialized with a small set of learnable mask tokens, which act as abstract starting points for mask generation. Through successive attention-based interactions, these tokens are refined by attending to both the image and prompt embeddings, ultimately producing one or more segmentation masks that align with the user’s intended region of interest.

The inclusion of initialized mask tokens is conceptually similar to the object queries used in Detection Transformers. Rather than predicting masks directly from the image, the decoder starts with a small, fixed number of abstract tokens and progressively refines them through interaction with image and prompt information. This interaction is achieved through attention mechanisms, allowing the decoder to reason jointly over what the image contains and what the user asked for.

A key design choice in SAM is that the mask decoder produces multiple candidate masks in a single forward pass. This is not an incidental detail, but a deliberate response to the inherent ambiguity of prompts. For example, a single click on an image might correspond to an entire object, a part of that object, or a smaller sub-region. By generating multiple masks along with confidence scores, SAM allows downstream systems, or human users, to select the most appropriate interpretation without requiring repeated inference.

Figure 1.3: Illustration of prompt ambiguity handling in the Segment Anything Model. From a single point prompt (green circle), SAM generates multiple valid segmentation masks in one forward pass, corresponding to different plausible interpretations of user intent.

From an architectural perspective, the division of labor within SAM is both clear and principled. The image encoder is dedicated to visual understanding, transforming the raw input image into a rich representation that captures spatial structure and semantic content. The prompt encoder focuses on modeling user intent, converting different forms of prompts such as points, boxes, or masks into embeddings that guide the segmentation process. The mask decoder then performs multimodal reasoning by jointly attending to the image embeddings, prompt embeddings, and learnable mask tokens in order to generate accurate segmentation outputs. This modular design not only improves interpretability by clearly separating concerns within the model, but also makes SAM highly extensible. Individual components can be independently replaced, scaled, or integrated with external systems such as vision language models without modifying the core segmentation framework.

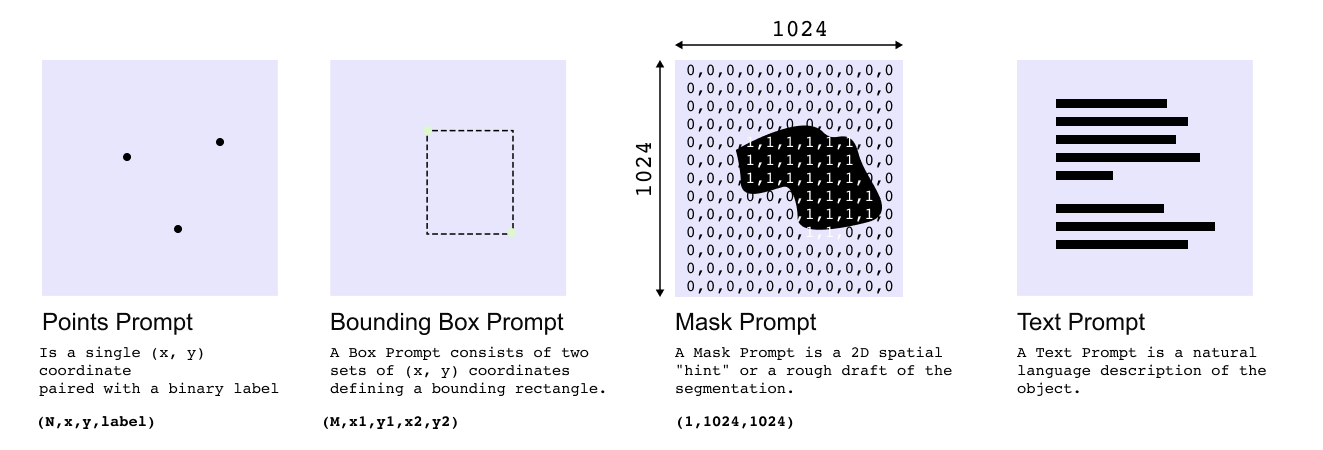

1.3 Prompting Mechanisms in the Segment Anything Model

Figure 1.4: Overview of prompt types supported by the Segment Anything Model, including point prompts, bounding box prompts, mask prompts, and text prompts. Point and box prompts provide sparse spatial cues, while mask prompts offer dense guidance, and text prompts are incorporated indirectly via external embedding models.

A defining feature of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) is its ability to perform promptable segmentation, where the segmentation output is guided by user-provided prompts rather than fixed semantic classes. These prompts act as signals of intent, specifying where or what the model should segment in an image. SAM supports multiple types of prompts, each differing in structure, information density, and level of user effort.

The most fundamental prompt type is the point prompt. A point prompt is represented as a single spatial coordinate (x, y) on the image, optionally paired with a binary label indicating whether the point belongs to the foreground or the background. Multiple points can be provided simultaneously to refine the user’s intent. Because point prompts consist of only a few discrete coordinates, they are referred to as sparse prompts. Despite their simplicity, point prompts are powerful, enabling intuitive interactions such as clicking on different regions of an image to progressively segment distinct objects or parts of objects.

A closely related prompt type is the bounding box prompt, which is defined by two corner coordinates (x1,y1) and (x2,y2). This prompt provides a coarse spatial constraint, indicating that the object of interest lies somewhere within the specified rectangular region. Like point prompts, bounding box prompts are sparse, as they rely on a small set of coordinates rather than dense spatial information. They are particularly useful when the approximate extent of an object is known but precise boundaries are not.

In contrast to sparse prompts, mask prompts are considered dense prompts. A mask prompt is a two-dimensional binary map, typically of the same spatial resolution as the input image, that provides a rough outline of the region of interest. Rather than specifying intent through isolated points or corners, mask prompts convey intent through a dense collection of pixels, offering stronger guidance to the model. Mask prompts are especially effective in refinement scenarios, where an approximate segmentation already exists and the goal is to improve its precision.

SAM also supports text-based prompts, but in an indirect manner. Text cannot be passed directly into the model. Instead, textual descriptions are first converted into embeddings using an external vision–language model, such as CLIP, which aligns text and image representations in a shared embedding space. These embeddings can then be fed into the prompt encoder in the same way as other prompt representations. As a result, text prompting in SAM depends on the availability of an external embedding model and is not natively supported in the core architecture.

Importantly, different prompt types can be used interchangeably or in combination, allowing flexible interaction patterns. Sparse prompts enable fast, lightweight user input, while dense prompts provide stronger constraints when greater precision is required. This unified prompt-based design allows SAM to generalize across tasks and domains without retraining, making it suitable for interactive segmentation, image editing, and downstream vision systems.

1.4 How the Dataset for SAM Was Created (Segment Anything 1B)

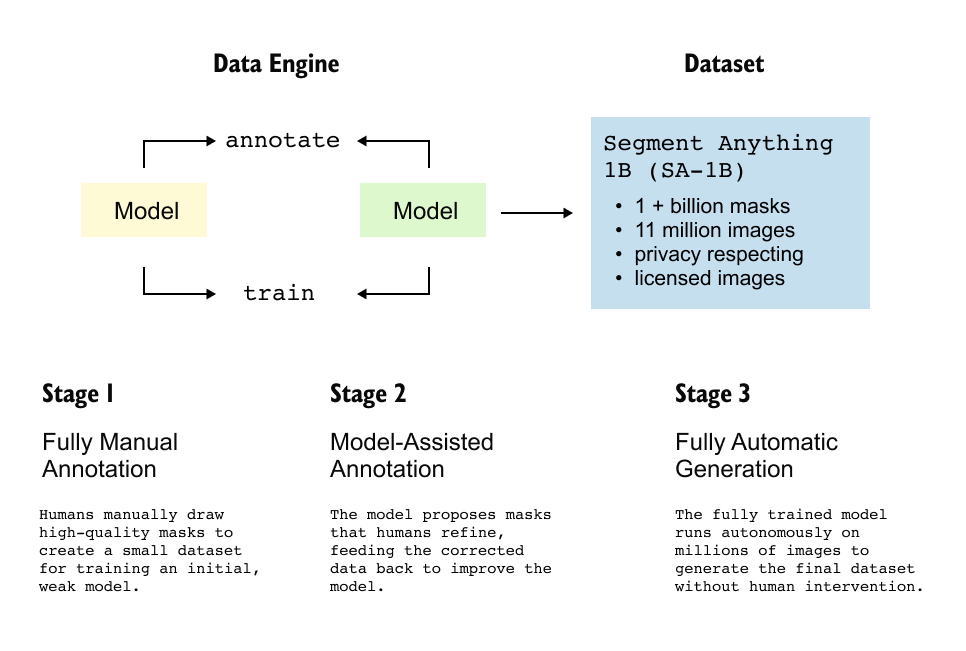

Figure 1.5: Three-stage data engine used to construct the Segment Anything 1B (SA-1B) dataset. The process transitions from fully manual annotation to model-assisted refinement and finally to fully automatic mask generation, producing over one billion segmentation masks at scale.

The success of the Segment Anything Model is not only a consequence of architectural design but also of the unprecedented scale and methodology used to construct its training dataset. The dataset, referred to as Segment Anything 1B (SA-1B), contains over 11 million images and more than 1.1 billion segmentation masks, making it one of the largest segmentation datasets ever created. Since manually annotating such a dataset is infeasible, the authors introduced a carefully designed three-stage data engine that progressively transitions from human annotation to full automation.

Stage 1: Fully Manual Annotation

The dataset creation process begins with a small but extremely high-quality seed dataset. In this stage, human annotators manually draw pixel-accurate segmentation masks for a limited number of images. These annotations are created entirely from scratch and represent expert-level, high-fidelity ground truth. While the quality of this data is very high, the quantity is necessarily small due to the cost and effort required for dense mask annotation. This dataset is used to train an initial version of SAM, which is relatively weak and limited in generalization capability but sufficient to begin the bootstrapping process.

Stage 2: Model-Assisted Annotation

In the second stage, the partially trained model from Stage 1 is used to assist humans in generating annotations. Instead of drawing masks from scratch, the model proposes segmentation masks based on simple prompts such as points or bounding boxes. Human annotators then refine these proposed masks by correcting inaccuracies or adjusting prompts when the model segments the wrong object. This correction-based workflow is significantly faster than full manual annotation. The refined masks and associated prompts are added back into the training set, and the model is retrained. This stage establishes an iterative human-in-the-loop process in which model quality and dataset size improve together.

Stage 3: Fully Automatic Mask Generation

The final stage removes humans from the annotation loop entirely. The improved model from Stage 2 is deployed at scale to automatically generate segmentation masks for millions of new images. On average, the model produces roughly 100 masks per image, covering objects, object parts, and regions at multiple levels of granularity. Although this stage introduces some noise and inaccuracies due to the absence of human verification, the sheer volume of data compensates for individual errors. Importantly, this stage also helps reduce human annotation bias, as the model often segments visual structures that humans might overlook or not consider salient.

All data from Stages 1, 2, and 3 are combined into a single large dataset, which is then used to train the final version of the Segment Anything Model. The authors explicitly note that the SA-1B dataset was created for training SAM itself, not as a standalone public benchmark. The dataset also adheres to privacy and licensing constraints, ensuring responsible large-scale data collection.

Overall, this three-stage data engine demonstrates how scalable supervision can be achieved by progressively shifting annotation responsibility from humans to models, enabling the creation of datasets at a scale that would otherwise be impossible.

1.5 Image Encoder in the Segment Anything Model

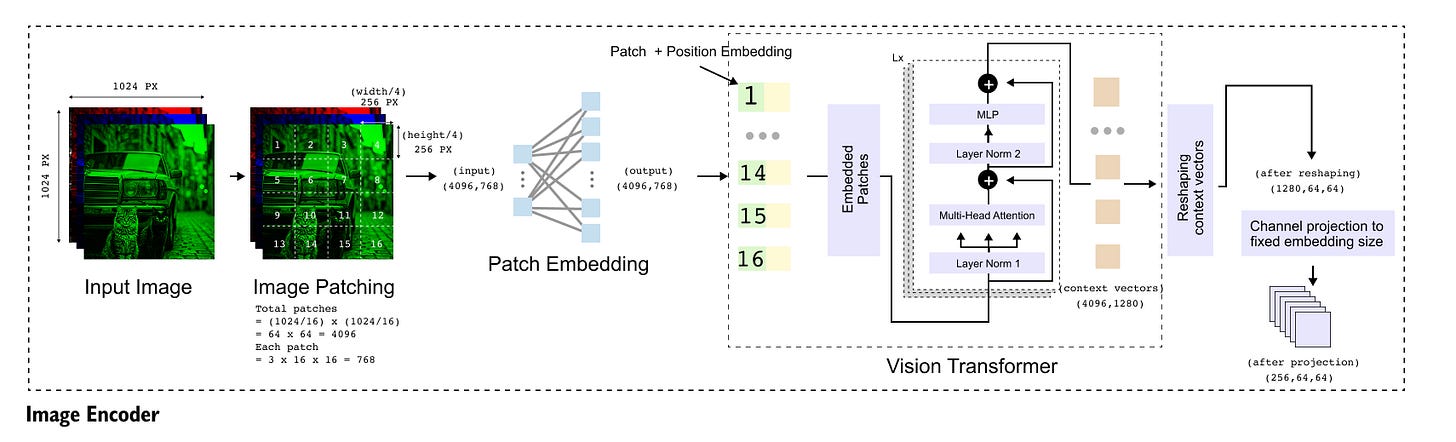

Figure 1.6: Detailed architecture of the SAM image encoder. A high-resolution input image is divided into 16 × 16 patches, projected into a 1280-dimensional embedding space, processed by a Vision Transformer, reshaped into a 64 × 64 spatial grid, and finally projected to a 256-channel feature map used by the mask decoder.

The image encoder is the first and computationally most intensive component of the Segment Anything Model. Its primary role is to convert a high-resolution input image into a compact, context-rich representation that preserves spatial structure while being suitable for downstream mask generation. In SAM, this is achieved using a Vision Transformer (ViT) that is pre-trained with a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) objective.

1.5.1 Input Representation

The input to the image encoder is a standard RGB image of shape

where 3 corresponds to the color channels and 1024 × 1024 represents the spatial resolution. This high resolution is intentionally preserved at the input stage to retain fine-grained visual details that are critical for precise segmentation.

1.5.2 Patchification

Following the standard Vision Transformer design, the input image is divided into non-overlapping patches of size

Each patch contains 16 × 16 × 3 = 768 values, accounting for spatial pixels and color channels. Since the image resolution is 1024 × 1024, this results in

patches in total. These patches are treated as a sequence of tokens, where the sequence length

and each token initially has dimensionality 768.

1.5.3 Patch Embedding and Positional Encoding

The raw patch vectors of shape

are not directly suitable for transformer processing because the Vision Transformer used in SAM operates in a higher-dimensional embedding space. Therefore, each patch vector is passed through a linear projection layer that maps it from 768 dimensions to 1280 dimensions, which is the embedding size of the ViT backbone. After this projection, the token representation becomes

Learnable positional embeddings are then added to these patch embeddings to encode spatial location information. This allows the transformer to reason about the relative and absolute positions of patches in the original image.

1.5.4 Transformer Encoding

The embedded patch sequence is processed by multiple transformer encoder layers. Through repeated self-attention and feed-forward operations, the model produces context vectors that capture long-range dependencies across the entire image. Importantly, the number of tokens remains unchanged during this process. The output of the transformer encoder therefore has the same shape as its input

where 4096 corresponds to the number of spatial tokens and 1280 is the embedding dimension.

1.5.5 Reshaping to Spatial Grid

Although the transformer processes tokens as a flat sequence, segmentation requires spatial structure to be preserved. To restore spatial organization, the token sequence is reshaped back into a two-dimensional grid.

Since 4096 = 64 × 64, the tensor is reshaped into

Here, 64 × 64 represents the spatial layout of patches, and 1280 corresponds to the feature channels at each spatial location. These features are no longer raw patches but context-enriched representations produced by the Vision Transformer.

1.5.6 Channel Projection to Decoder-Compatible Space

The embedding dimension of 1280 is appropriate for the Vision Transformer but does not match the expected input dimension of the mask decoder. To resolve this, a final linear projection is applied independently at each spatial location to reduce the channel dimension from 1280 to 256. After this projection, the final output of the image encoder has shape

This representation can be interpreted as a dense feature map with 256 channels and reduced spatial resolution, analogous to the output of a deep convolutional backbone.

1.5.7 Summary of Image Encoder Transformation

The complete transformation performed by the image encoder can be summarized as:

During inference, this expensive computation is performed only once per image. The resulting feature map can be reused across multiple prompts, which is a key reason why SAM supports fast and interactive segmentation.

1.6 Masked Autoencoder Pretraining for the SAM Image Encoder

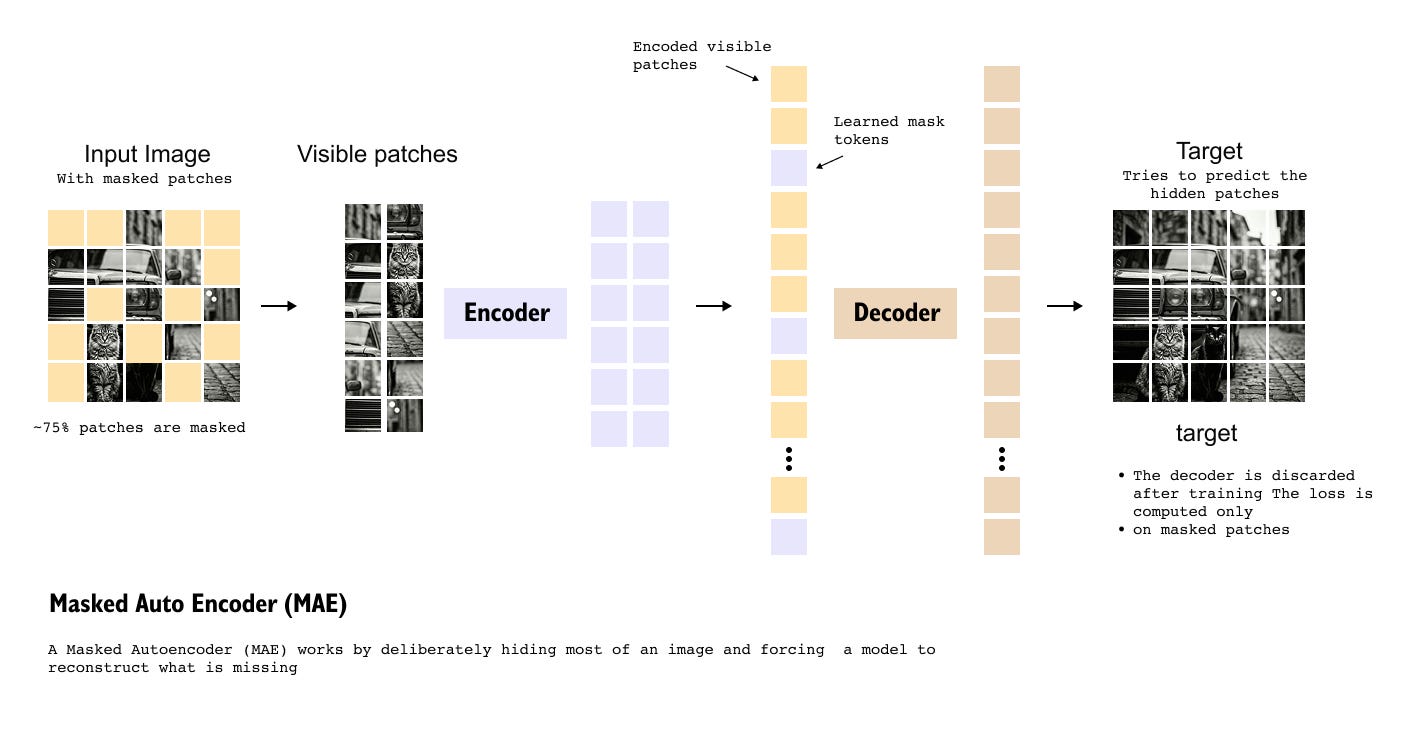

Figure 1.7: Masked Autoencoder (MAE) pretraining framework used for the SAM image encoder. A large portion of image patches is masked, visible patches are encoded using a Vision Transformer, learnable mask tokens represent hidden patches, and a decoder reconstructs the missing content. After training, only the encoder is retained for use in SAM.

The Vision Transformer used in the Segment Anything Model is not trained from scratch on segmentation data. Instead, it is pre-trained using a Masked Autoencoder (MAE) objective. This pretraining strategy plays a crucial role in enabling the image encoder to develop strong visual representations that generalize well across objects, scenes, and spatial structures.

1.6.1 Motivation Behind Masked Autoencoders

A masked autoencoder is a self-supervised learning framework designed to force a model to deeply understand the structure of images rather than memorize labels. The central idea is simple: hide most of the image and train the model to reconstruct what is missing. If the model can accurately predict large missing regions using only partial information, it must have learned meaningful visual patterns and global context.

This idea is directly analogous to masked language modeling in models such as BERT, where words are hidden and the model learns to predict them from surrounding context. In MAE, however, the basic units are image patches instead of words.

1.6.2 Patch Masking Strategy

The input image is first divided into patches in the same way as a standard Vision Transformer. From this set of patches, a large fraction, typically around 75 percent, is randomly masked. Only the remaining 25 percent of patches are kept visible.

These visible patches are converted into patch embeddings and passed to the encoder. The masked patches are completely removed from the encoder input, which significantly reduces the computational cost during training.

1.6.3 Encoder Processing

The encoder receives only the visible patch embeddings and processes them using a Vision Transformer. Since the encoder sees only a small subset of patches, it is forced to extract as much contextual information as possible from limited input. The output of the encoder consists of embeddings corresponding only to the visible patches.

At this stage, the model has no direct information about the masked regions, yet it must infer what could plausibly exist there based on global structure, object continuity, and visual patterns.

1.6.4 Learnable Mask Tokens and Decoder

To reconstruct the original image, the encoded visible patch embeddings are combined with a set of learnable mask tokens, one for each masked patch. These mask tokens do not contain image information initially. Instead, they serve as placeholders that the model must learn to fill in.

The combined sequence of visible patch embeddings and mask tokens is then passed through a decoder, which attempts to reconstruct the pixel values of the original image. The decoder predicts the content of all patches, but the reconstruction loss is computed only on the masked patches. This design choice prevents the model from simply copying visible information and forces it to learn meaningful representations.

1.6.5 Training Objective and Representation Learning

At the beginning of training, the reconstructed patches differ significantly from the true pixel values, leading to high reconstruction loss. As training progresses, the encoder learns increasingly informative representations, and the decoder becomes better at predicting the hidden patches.

Through this process, the Vision Transformer encoder becomes highly effective at capturing global image structure, object boundaries, textures, and spatial relationships. Importantly, the goal of MAE pretraining is not classification, but visual understanding. Unlike traditional Vision Transformers that rely heavily on a class token, MAE leverages all patch embeddings, making it particularly suitable for dense prediction tasks such as segmentation.

1.6.6 Role of MAE in SAM

After pretraining, the decoder used in the masked autoencoder is discarded. Only the pre-trained Vision Transformer encoder is retained and reused as the image encoder in SAM. This encoder provides rich, context-aware feature maps that form the foundation for promptable segmentation.

Because the encoder has been trained to reason about missing image regions, it is exceptionally well-suited for tasks that require precise spatial understanding, such as predicting segmentation masks from sparse prompts.

1.7 Prompt Encoder in the Segment Anything Model

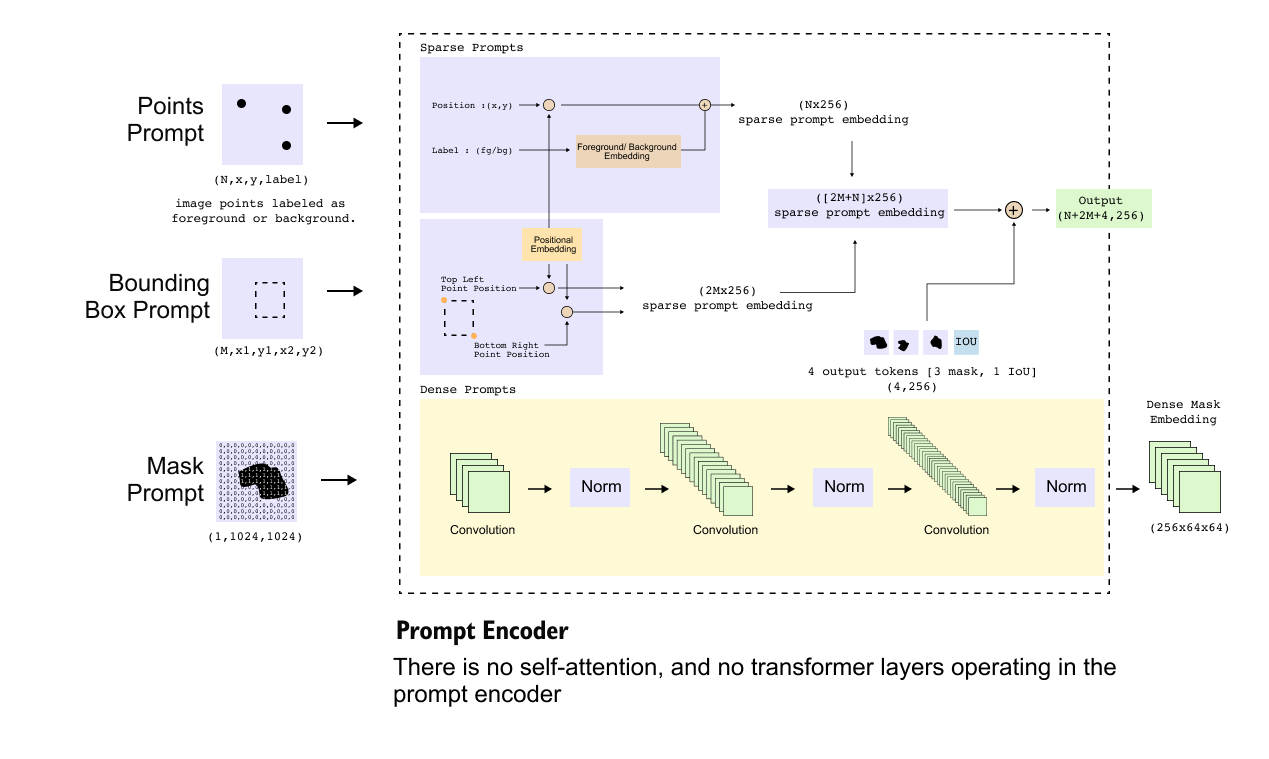

Figure 1.9: Internal representation produced by the prompt encoder. Sparse prompts are converted into a token sequence and concatenated with learnable output tokens, while dense mask prompts are fused with image embeddings via element-wise addition before entering the mask decoder.

After the image encoder produces a spatially structured feature map, the second major component in SAM is the prompt encoder. The role of the prompt encoder is to translate user-provided prompts into embeddings that can guide the mask decoder toward the intended object or region. Unlike the image encoder and the mask decoder, the prompt encoder is intentionally lightweight and does not contain any transformer layers or self-attention mechanisms. Its design reflects the fact that prompts carry explicit semantic intent and do not require heavy contextual reasoning on their own.

All prompt representations are converted into a 256-dimensional embedding space, since 256 is the interface dimension expected by the mask decoder and matches the projected output of the image encoder.

1.7.1 Sparse Prompt Tokenization

Sparse prompts, namely points and bounding box corners, are converted into token embeddings. Each token corresponds to a single geometric entity and occupies one position in a token sequence.

Each sparse prompt is ultimately represented as a token formed by combining three elements. First, the normalized geometric coordinates are projected into a 256-dimensional embedding space so that they match the dimensionality expected by the decoder. Second, a learnable positional embedding is added to refine spatial bias beyond the raw coordinate values. Third, a learnable type embedding is included to encode the semantic role of the token, indicating whether it corresponds to a point prompt, the first corner of a bounding box, or the second corner. After this encoding step, point prompts are represented as a tensor of shape (N, 256), while bounding box prompts are represented as a tensor of shape (2M, 256), reflecting the fact that each box contributes two corner tokens. These sparse tokens are not handled in isolation; instead, they are concatenated along the token dimension to form a single sparse prompt sequence of length N + 2M, which is then passed downstream to guide mask generation.

1.7.2 Dense Prompt Encoding and Fusion

Dense mask prompts are treated fundamentally differently. Rather than producing tokens, the mask prompt encoder outputs a spatial feature map of shape

This representation is intentionally aligned with the image encoder output, which also has shape (256, 64, 64). Because of this alignment, dense prompt information is not concatenated with tokens. Instead, it is fused with image features via element-wise addition.

This operation directly injects spatial guidance from the mask prompt into the image embedding, ensuring that dense cues influence every spatial location before decoding begins.

1.7.3 Output Tokens for Mask Generation

In addition to prompt-derived embeddings, the mask decoder requires a fixed number of learnable tokens to initiate mask generation. SAM predicts three candidate masks and one IoU score vector, which together require four output tokens.

These tokens are randomly initialized learnable vectors, each with a dimensionality of 256, and they do not originate from either the prompt encoder or the image encoder. Instead, they are introduced solely to initialize the decoding process and provide fixed starting points for prediction. Conceptually, they play the same role as object queries in detection transformers, acting as abstract placeholders that are progressively transformed by the decoder into meaningful outputs, namely the final segmentation masks and their associated quality scores.

1.7.4 Final Token Sequence Construction

Before entering the mask decoder, the token representations produced so far are assembled into a single sequence. The sparse prompt tokens, which have shape (N + 2M, 256), are concatenated with a fixed set of output tokens of shape (4, 256). This concatenation results in a unified token sequence of shape (N + 2M + 4, 256), which serves as the sequential input to the decoder. In parallel, the spatial input to the decoder is constructed by element-wise addition of the image encoder output and the dense mask prompt embedding, both of which have shape (256, 64, 64). This addition fuses visual features with dense spatial guidance when a mask prompt is provided. Together, the token sequence and the spatial feature map fully specify the information that is passed into the mask decoder.

The prompt encoder does not perform multimodal reasoning. Instead, it acts as a structural adapter, converting prompts into decoder-compatible representations. All semantic interaction between image content, user intent, and output hypotheses is deferred to the mask decoder. This clear separation of responsibilities is a central reason why SAM remains both extensible and efficient for interactive segmentation.

1.8 Mask Decoder

Figure 1.10: Architecture of the SAM mask decoder. The decoder takes a token sequence and a spatial image feature map as inputs, applies self-attention and bidirectional cross-attention, upsamples image features, and generates multiple segmentation masks using per-mask dot products, along with IoU confidence scores.

The mask decoder is the only component in SAM that performs full transformer-based reasoning. Its role is to combine visual information from the image encoder with prompt-derived tokens and transform them into final segmentation masks along with corresponding IoU confidence scores. Architecturally, the decoder operates on two parallel inputs: a token sequence and a spatial image feature map, each carrying complementary information.

1.8.1 Inputs to the Mask Decoder

The first input is a token sequence of shape (N + 2M + 4, 256). This sequence consists of sparse prompt tokens derived from points and bounding box corners, together with four learnable output tokens. Among these four tokens, three are dedicated to producing segmentation masks and one is dedicated to predicting IoU scores. Each token is a 256-dimensional vector, and the sequence length reflects the total number of sparse prompts plus the fixed output queries.

The second input is a spatial feature map of shape (256, 64, 64). This map is obtained by element-wise addition of the image encoder output and the dense mask prompt embedding, if a mask prompt is provided. Both inputs share identical dimensionality, which allows them to be fused directly. For transformer operations, this spatial map is temporarily reshaped into a sequence of 4096 tokens, each of dimension 256, corresponding to the flattened 64×64 grid.

1.8.2 Transformer Structure and Attention Flow

The core of the mask decoder is a transformer block that is repeated twice in series. Each block contains four stages: self-attention over tokens, token-to-image cross-attention, a feed-forward MLP, and image-to-token cross-attention.

The process begins with self-attention applied only to the token sequence. Queries, keys, and values are all derived from the same token set, allowing prompt tokens and output tokens to exchange information and form context-aware representations. The output of this stage remains a sequence of length N + 2M + 4, with each token still embedded in 256 dimensions.

Next, token-to-image cross-attention is performed. In this stage, the token sequence generates the queries, while the flattened image feature sequence generates the keys and values. This allows each token to attend over all spatial locations in the image. Importantly, the number of output context vectors produced here equals the number of queries, not the number of image tokens. As a result, the output remains a sequence of N + 2M + 4 tokens, now enriched with image context.

Following this, an MLP is applied independently to each token to further refine the representations. After the MLP, image-to-token cross-attention is applied. In this case, queries are generated from the image feature sequence, while keys and values come from the token sequence. This operation propagates prompt information back into the image features. The output of this step is a sequence of 4096 image tokens, each of dimension 256, which is then reshaped back into a spatial tensor of shape (256, 64, 64).

This entire transformer block is executed twice, allowing for deeper bidirectional interaction between token representations and spatial image features.

1.8.3 Image Upscaling Path

After the transformer blocks, the refined image feature map of shape (256, 64, 64)is passed through an image upscaling module. This module consists of two successive convolutional upsampling operations, each doubling the spatial resolution. As a result, the feature map is transformed first to (256, 128, 128) and then to (256,256,256). This higher-resolution feature map is used for precise mask generation.

1.8.4 Mask and IoU Prediction

At this stage, only the four output tokens are retained from the token sequence. The token dedicated to IoU prediction is passed through a small MLP to produce IoU scores for the predicted masks.

Each of the three mask tokens is processed independently through its own MLP, producing three vectors of dimension 256. These vectors act as dynamic mask heads. For each mask token, a per-mask dot product is computed between the 256-dimensional token vector and the 256-channel upscaled image feature map. This operation collapses the channel dimension, producing a single-channel spatial mask of shape (1, 256, 256).

Finally, each mask is resized using interpolation to match the original image resolution, resulting in output masks of shape (1, 1024, 1024). The decoder therefore produces three candidate segmentation masks along with corresponding IoU scores, enabling the model to represent multiple plausible segmentations for ambiguous prompts.

1.9 Conclusion Perspective on SAM

Figure 1.11: Bird’s-eye view of the Segment Anything Model architecture. The image encoder extracts visual embeddings, the prompt encoder encodes user guidance, and the mask decoder combines both to generate valid segmentation masks.

The Segment Anything Model represents a clean and principled rethinking of image segmentation as a prompt-driven, general-purpose task. By clearly separating visual understanding, user intent, and mask generation into the image encoder, prompt encoder, and mask decoder, SAM achieves both flexibility and scalability. The image encoder learns strong, general visual representations through masked autoencoder pretraining. The prompt encoder translates diverse user inputs into a unified embedding space without relying on transformers. The mask decoder then performs multimodal reasoning using bidirectional attention to fuse image features with prompts and produce multiple plausible masks along with confidence scores.

This modular design enables SAM to handle ambiguity, support multiple prompt types, and generalize across datasets without task-specific retraining. More importantly, it establishes a reusable architectural pattern where segmentation becomes an interface problem rather than a fixed-label prediction task. As a result, SAM serves not only as a powerful segmentation model but also as a foundation for interactive vision systems and downstream vision language applications.

Watch the full lecture video here

If you would like to deepen your understanding of Segment Anything Model (SAM) and see these ideas explained visually and intuitively, you can refer to the accompanying video linked above. If you wish to get access to our code files, handwritten notes, all lecture videos, Discord channel, and other PDF handbooks that we have compiled, along with a code certificate at the end of the program, you can consider being part of the pro version of the “Transformers for Vision Bootcamp”. You will find the details here:

https://vision-transformer.vizuara.ai/

Other resources

If you like this content, please check out our research bootcamps on the following topics:

CV: https://cvresearchbootcamp.vizuara.ai/

GenAI: https://flyvidesh.online/gen-ai-professional-bootcamp

RL: https://rlresearcherbootcamp.vizuara.ai/

SciML: https://flyvidesh.online/ml-bootcamp

ML-DL: https://flyvidesh.online/ml-dl-bootcamp

Connect with us

Dr. Sreedath Panat

LinkedIn : https://www.linkedin.com/in/sreedath-panat/

Twitter/X : https://x.com/sreedathpanat

Mayank Pratap Singh

LinkedIn : www.linkedin.com/in/mayankpratapsingh022

Twitter/X : x.com/Mayank_022.